As a child in Wales, I walked to church three times every Sunday.

St Michael’s church – Llanfihangel Genau’r Glyn – had stood at the top of the village since Norman times, nestled beside an ancient forest. A yew tree in the graveyard was said to be two thousand years old. Mattins was at 9.30 am. Sunday school in the afternoon, and Evensong at six. Dressed in cassock, surplice, and ruff, I sang in the choir, then sat quietly while the vicar recited the prayers and gave his sermon. Perhaps it was here that I discovered the pleasures of boredom, gazing around and imagining stories about the colourful figures in the stained-glass windows (the saint skewering a poor dragon with his lance; the handsome young captain who had died in the Great War). It was here that I fell in love with the sounds and cadences of English through the language of the King James Book of Common Prayer.

For the Lord is a great God: and a great King above all gods.

In his hands are all the corners of the earth: and the strength of the hills is his also.

The sea is his, and he made it: and his hands prepared the dry land.

O come, let us worship and fall down: and kneel before the Lord our Maker.

For he is the Lord our God: and we are the people of his pasture, and the sheep of his hand.

At Christmas time, I walked with the choir through falling snow, carrying a lantern on a staff, to sing carols at local farmhouses before being ushered into the bright kitchens for hot drinks and mince pies. In summertime, the long evenings were often spent at the vicarage (eighteenth-century, ivy-covered) playing tennis with the vicar’s four, equally adorable, teenaged daughters.

By the age of fourteen, though, a stern voice within me brought all this to an end. Religion was superstitious nonsense, I told my mother in a curt, patronising tone. The idea of an all-powerful creator was no more than a pathetic delusion. I attended church no longer. Coincidentally, the vicar and his family moved to another parish around this time. There were no more summer evenings flirting on the vicarage tennis court.

•

My views on religion were unchanged when I recently came to read Chris Tsiolkas’ 2019 novel, Damascus. (I let books rest for a few years after publication, so my reading isn’t polluted by reviews or dinner-table conversation). Having written about early Christian history, I was interested in how Tsiolkas (a non-believer like me) would approach the story of St Paul. The Apostle is renowned for his influential epistles, for shaping early Christianity, and taking it beyond the Jewish world. He is also known for his emphasis on Original Sin and his views on women and sexuality which jar with contemporary attitudes.

Tsiolkas is interested in exploring the conflict within Paul rather than making simplistic judgments. The novel begins with a young Christian woman being stoned to death by religious Zealots for the crime of having sex outside marriage. The scene is brutal and painful to read. Only when the smashed body of the woman lies dead do we discover that Paul has been watching. It was he who exposed her ‘crime’. Paul’s actions, we begin to learn, are an externalisation of guilt and hatred of himself for his homosexuality and lust (a possibility much discussed in theological writings). The tale unfolds with Tsiolkas’ customary skill and economy of detail. It leaps across decades, locales, and protagonists, to present a rounded portrait of Paul at different stages of life: transformed by his vision of Christ on the road to Damascus; travelling the Roman Empire to spread the word that a Second Coming is imminent, and that becoming a Christian brings eternal salvation. In the novel, Paul surrenders to Christ’s message of universal love, and is prepared for his imminent return, the ‘end time’. At the story’s end, Paul has died, and his companion, Timothy, is an old man approaching his own end. They have done their task well, however, with the seeds of Christianity planted over half the Roman Empire. At the same time, factionalism and differences within the Church hint at troubled times to come.

Tsiolkas is masterful and empathetic in conveying the conflict in Paul’s mind, and the power of his impact as an evangelist. Yet I could not help being revulsed at observing the birth of the Church – not only because it infused natural instincts with guilt and shame and became such an oppressive instrument of the powerful (from the Emperor Constantine to Putin in the present day), but because belief in an all-powerful creator is simply irrational nonsense, a cruel delusion foisted on the vulnerable, alienating them from power over their own lives. At the same time, we can understand its appeal to people struggling in poverty or distress of any kind, especially slaves in ancient Rome or antebellum America. The message is essentially, ‘Yes, your life is miserable and that won’t change. But obey the Church’s laws and you will be reborn and live eternally after you die’. For people in difficult physical or mental straits, this is a seductive offer. In Nietzsche’s acerbic words, ‘Christianity was from the beginning, essentially and fundamentally, life’s nausea and disgust with life, merely concealed behind, masked by, dressed up as, faith in “another” or “better” life.’ Nietzsche, by the way, was always careful to distinguish between the Christianity of the Church and the actual message of Jesus Christ, of loving kindness to all humanity (a kindness so lacking in my own brutal words to my mother).

There’s more to it than this, however. Whatever their circumstances, humans have always needed to understand existence within some overall framework that seems to make sense of their experience, a schema into which they snugly fit. It’s their place in the world. Our sense of self turns out to be a fragile thing. This has become evident in recent years as large numbers of people have become unmoored from reality, coping with the stress of a global pandemic by clinging to risible conspiracy theories and even taking violent action inspired by them. Religion is mocked with cheap jibes by atheists such as Richard Dawkins, but as a scientist shouldn’t he recognise that people indisputably have a need for such an epistemological framework?

This need does not evaporate for people who are fortunate to live in a society like ours which is democratic, rational, and educated. Instead we become invested with a confidence in science (as happened overwhelmingly in Australia during the pandemic) and a framework of liberal values (including human rights) which begin to assume the infallible ‘natural’ authority of Mosaic laws.

It takes a further leap, perhaps, to face the fact that there is no objective, universal framework to our lives. The universe has no purpose. Life is merely an accident which seeks to perpetuate itself. Death is certain. As Camus wrote:

All that remains is a fate whose outcome alone is fatal. Outside that single fatality of death, everything, joy or happiness, is liberty. A world remains of which man is the sole master. What bound him was the illusion of another world.

For Camus, accepting the senselessness of the world is the first step; the next is to take responsibility for making our own sense of it. But do we have the courage to do this, to forego the comforting fantasies of religion and other absolutist schema? Would St Paul have embraced the Christian message if faced with the knowledge that there is no God and that death is final? How much more impressive that would be – to do good for its own sake, not as a transaction, as a down-payment for eternal life.

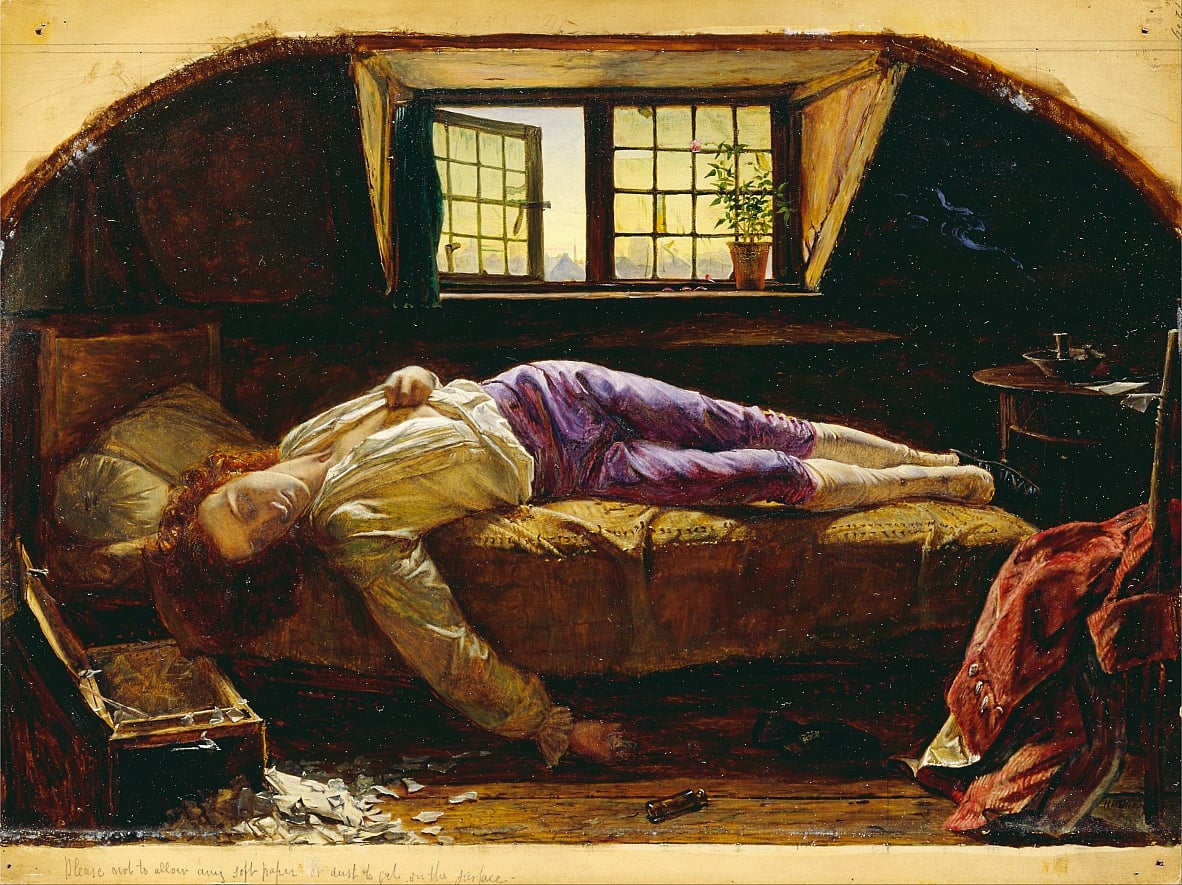

Image: Caravaggio. The Conversion of St Paul (1601).

Written by : Paul Morgan

2 Comments

Comments are closed.

Hi Paul

Merry Xmas to you and Caroline.

I very much enjoyed your meditation triggered by reading Damascus.

I agree with your view that the universe has no purpose, and that life is merely an accident which seeks to perpetuate itself.

So it seems to me that part of being human is to give life purpose – our disparate purposes. The US writer Cory Panshin has written a fascinating exploration of how we ascribe meaning. If you haven’t seen it, I’ve attached it to this email.

Best wishes

Rob

>

Thanks Rob, will check out Panshin. To be discussed!