Review of Travelling Companions by Antoni Jach (Transit Lounge, 2021)

Travelling Companions is a book made to read in lockdown. We Australians are renowned travellers. The year spent backpacking after university is a rite of passage, and we think nothing of flying 1,000 km and back for a lunch meeting in Sydney or Melbourne. Being locked in ‘Fortress Australia’ for a second year is especially frustrating, therefore (though trivial compared to the impact of COVID-19 on many other countries, of course). The next best thing to a Qantas ticket, then, is a vicarious journey through Europe is the company of a master storyteller.

This is the plot of Antoni Jach’s new work, describing a journey which starts in Barcelona and curves across Europe to end in Rome where the narrator flies home to Melbourne again. He meets various other travellers from around the world who tell stories to each other, especially Nina, an alluring Milanese whose tales are ever more extraordinary and captivating. Any reader expecting an easy ride on a travelogue is soon disappointed. The intial train journey to Avignon is delayed, then postponed; the travellers are turned back to their starting point before setting out a second time by bus, only to be held up yet again by French farmers who have blockaded the autoroute. The bus turns back . . . it feels like there are more delays and digressions here than in chapter one of Tristram Shandy. What can the passengers do but pass the time by telling stories?

We hear from a Dutch commercial traveller haunted by his ancestors’ wealth being built on colonial exploitation in Java. A postman in Poland steals and opens love letters, making ‘improvements’ before re-sealing and sending them on their way. There is a stockbroker who moonlights as a courtesan offering the expensive SGE (Superior Girfriend Experience). A philosopher who turns to the family business of art forgery. We also learn about the travellers’ lives, the story of the historical sites they visit, and much more besides. It soon becomes clear, though, that something odd is happening. Set in 1999, it’s remarkable how the journey feels like another epoch when the characters cannot stay in touch by mobile phone, before they can use a single currency throughout Europe, or make flight and accommodation bookings via apps instead of queuing at a travel agency or struggling through a telephone conversation in another language to a distant hotel. It’s more than this though . . .

As well as acutely observed characters and situations, there is something delightfully artful going on. The same details crop up in different tales told by different people. A reference to Pinoccio. Clairefontaine notebooks. In Venice, the narrator dreams of a ring and finds one on a footpath the following morning . . . he gives it to an Australian girl who returns it to him in another city . . . an American companion plans to give his girlfriend a ring in the hope she will marry him, but she refuses to accept it and walks onto her plane and out of his life. The recurring details, circling stories, and performance of departures and returns, make Travelling Companions more reminscent of oral storytelling than a compact modern novel. The narrator carries Bocaccio’s Decameron with him, but his tale hints at a far older, pre-literate tradition, when travelling storytellers would recite a long chain of stories linked by a subtle thread, such as Scheherazade, for example. The need for story is deeply ingrained in human cultures, whether narratives around millenia-old rock art or the latest must-see TV serial such as Mare of Eastwick. Stories make sense of the random data of everyday life. They place us in space and time. We recognise the characters and situations and feel that, perhaps, we are not alone in the solitary confinement of our skulls after all.

Travel itself is a kind of story. On the road, we are living a narrative with an intense awareness of having been somewhere different yesterday, and that we’ll be somewhere else tomorrow. Everything is new. Away from our usual habitat, there is a heightened sense of existence as Jach’s narrator recognises. We give ourselves permission to be someone a little different if we want, and permission to watch others and our surroundings more closely. ‘I’m like blotting paper’ soaking up impressions, Jach writes, and ‘I’m just a solitary traveller looking for people to talk to, so I don’t fall off the edge of the flat earth’.

Reading Travelling Companions began to remind me of watching a Fellini movie, so it was no surprise when one of Jach’s characters exclaimed, ‘my life feels like 8½ or La Dolce Vita . . .’ In unfamiliar surroundings, his characters undergo metamorphoses like Fellini’s, transformed by the tales they hear and of which they are a part. ‘We hold our personalities together with paperclips,’ Jach writes, ‘and those paperclips are the stories we tell each other.’

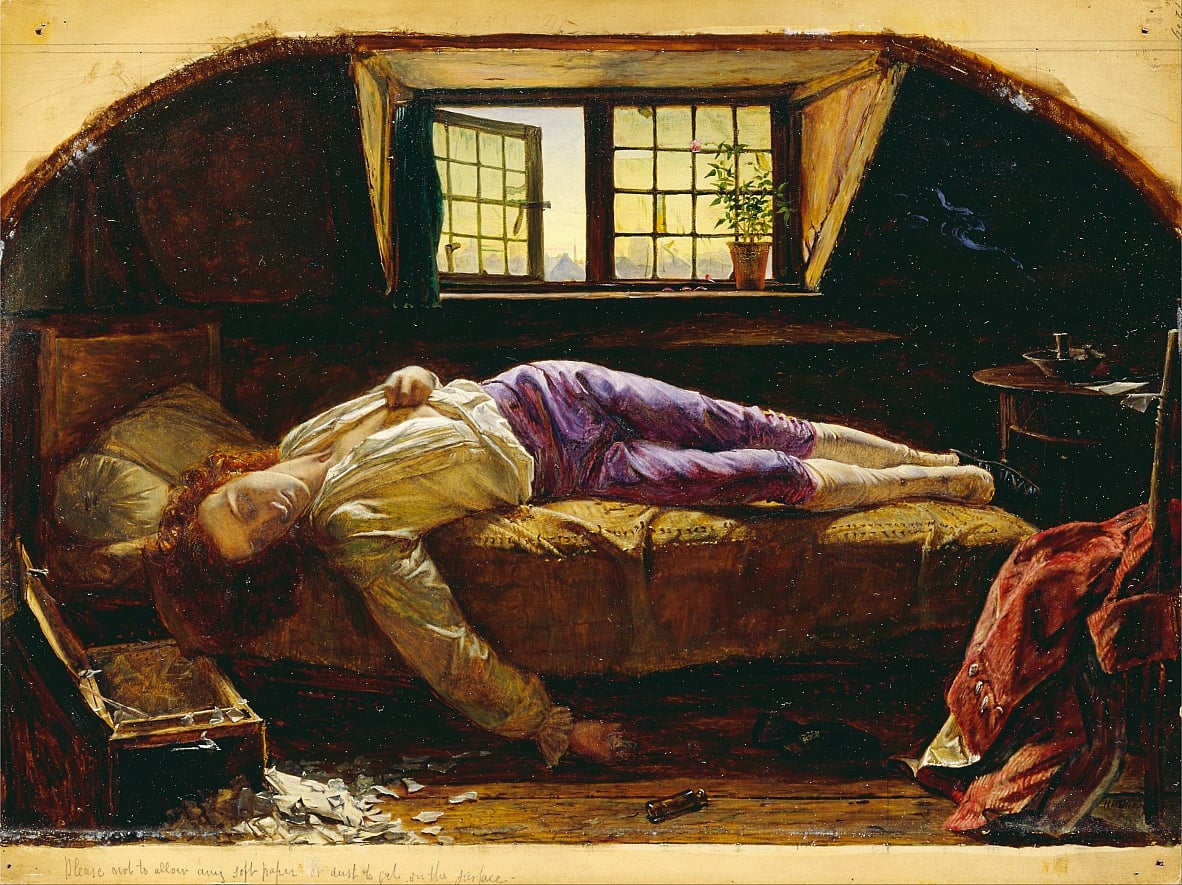

At one point, the travellers stand in a Venetian art gallery before Gorgione’s The Tempest, famously one of the most mysterious paintings ever created. In the foreground, a woman on the right suckles a child at her breast. She is nude, with her pubic area visible, yet the impression is of innocence and trusting vulnerability, not sexual display. On the left stands a young man with a pike, well dressed and looking pleased with himself. They do not look at each other; in fact, each seems to inhabit their own space. In the background a storm looms over a city which might be Padua as lightning crackles across the sky. Jan Morris called it ‘a haunted picture’. The Tempest is an enigma which viewers must construct their own stories to explain. For the characters and readers of Travelling Companions too, it is stories which make sense of our lives – the lies that tell the truth.

________________________________________________________