When Francis Bacon’s Three studies of Lucian Freud was auctioned at Christie’s, the painting sold for a remarkable $127 million. Bacon is not only one the most valued painters of the past 100 years (by the crude index of auction price), he is also established as one of the most significant artists of the twentieth century. A major new exhibition at the Pompidou Centre in Paris focuses on the artist’s late period from 1971 until his death in 1992.

Bacon. En toutes lettres (11 September – 20 January 2020) includes 60 paintings, with 12 triptychs. In side-chambers, readings which inspired Bacon can be heard: passages from Aeschylus, Nietzsche, George Bataille, T S Eliot, and others – carefully selected from the artist’s library by the Pompidou’s Didier Ottinger. There is more than one trap for curators when attempt to provide an exhibition with structure. Telling a simplistic story with a rigid time-line. Being over-reverent. ‘Padding out’ with works which don’t add to an exhibition’s value. Worst of all, imposition of a rigid interpretive perspective, making it harder for the viewer to come to a personal relationship with a work of art – to see it for ourselves.

Ottinger falls into none of these traps curating Bacon. En toutes lettres. The high, wide spaces allow the works to ‘breathe’ with sufficient space around them for comfortable contemplation. Labels are discreet and minimal. The book readings provide an interesting context but are not overbearing. Bacon’s paintings are left to speak for themselves. Yet they do not simply speak. They roar. They howl. They sing sweetly and weep and scream out in defiance. This exhibition is an explosion, a spectacular display of Francis Bacon’s creativity in the last twenty years of his life.

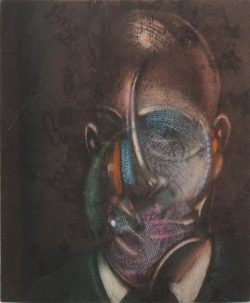

The paintings are notably different from his earlier work: sparer, more refined, and using a smaller palette of intense colours. With Bacon, we are reminded of the human body in the bloody process of being born, in the throes of sex or death, or perhaps in an operating theatre or torture chamber. We look away, then are compelled to look again. Bacon’s cool, unblinking gaze is turned onto his own grief and suffering too. A posthumous portrait of his lover, George Dyer, is especially moving. One panel of the triptych shows Dyer as a defeated boxer, twisted and bloodied on the floor, hardly recognisable as a person. Many works are coloured by the sexuality which Bacon, recognises as integral to our existence and identity. He lived for most of his life in an era when homosexuality was cruelly persecuted, yet was defiantly, brazenly proud of who he was. Bacon understood sexuality not in a narrow physiological or legalistic way, but as an acceptance and delight in our physical existence. Through all of his works, we sense this delight as well as evocation of the fear and revulsion we can feel at this mirror held up to human life and our mortality.

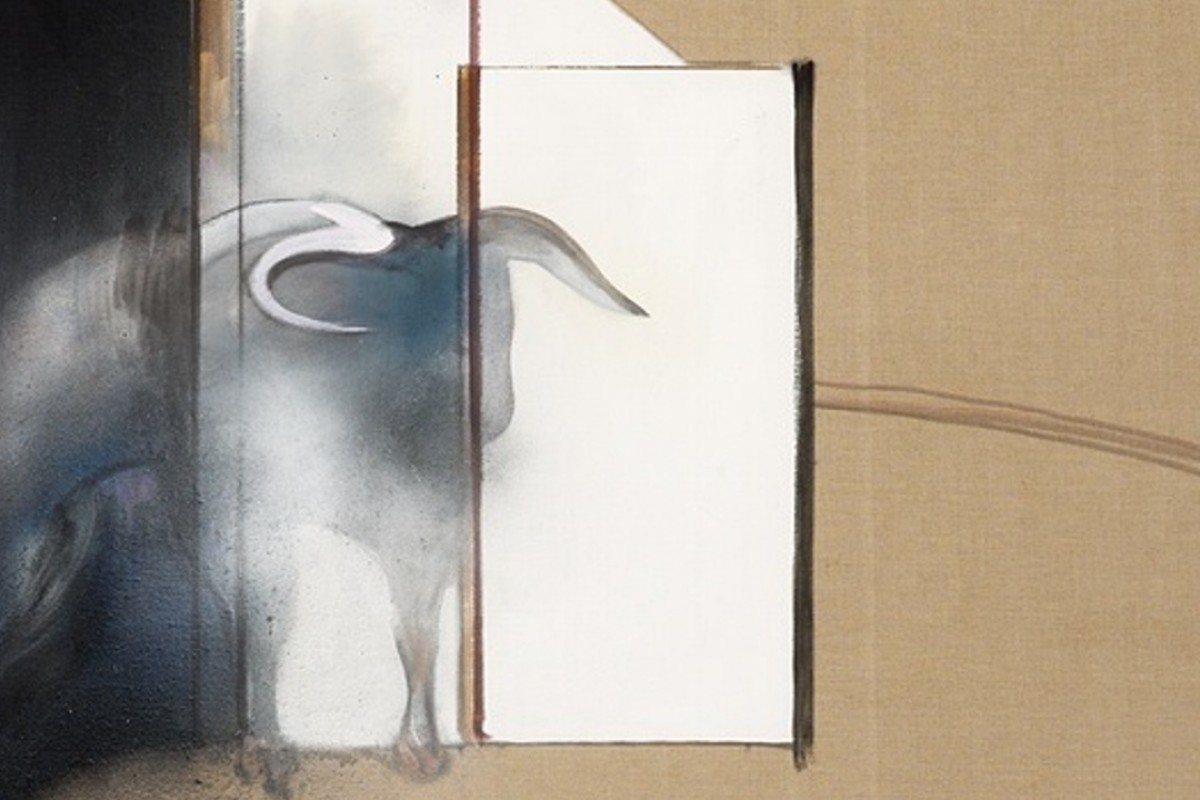

The final painting in the exhibition is Study of a Bull, completed a few months before Bacon’s death. The bull hovers translucently at a doorway. Behind him is sheer blackness, before him the plain background of what may be a bullring. (The dying Bacon rubbed dust from his studio floor into the painting here, a reminder of his own mortality.) The door is a bright rectangle of light. Is the bull going forward into this? Retreating into the blackness? Or is the flickering, part-transparent bull doing both? The creature is transfixed in time. Study of a Bull is a masterpiece, evoking the mystery of human existence, providing no answers, but asking all the right, thrilling questions. Bacon wrote that he hoped through art ‘to crystallise time, in the same way as Proust did in his novels’. Bacon. En toutes lettres also reminded me forcefully of a passage by Vladimir Nabokov. It could have been written in flames at the entrance to this astonishing exhibition:

Let all of life be an unfettered howl. Like the crowd greeting the gladiator. Don’t stop to think, don’t interrupt the scream, exhale, release life’s rapture.

For more details of the exhibition, see the Pompidou Centre website.

Images

Triptych – In Memory of George Dyer (1971)

Portrait of Michel Leiris (1976)

Study of a Bull (1991)

Great stuff. Bacon remains my favorite artist of the 20th century. I noted that you correctly, I think, observed in his portrait of Michel Leiris that, “the uncomfortable realisation of our own fragility: that we are embodied beings trapped for life in a carcase of meat and destined to die, eaten up by time.”

Many a recent critic hs missed the point of Bacon and accused that his work is a “slaughterhouse” and that he portrays people as meat only. They leave out the “beings” emodied in the meat.

You gottit. Really like your piece on Bacon and Freud too by the way :)